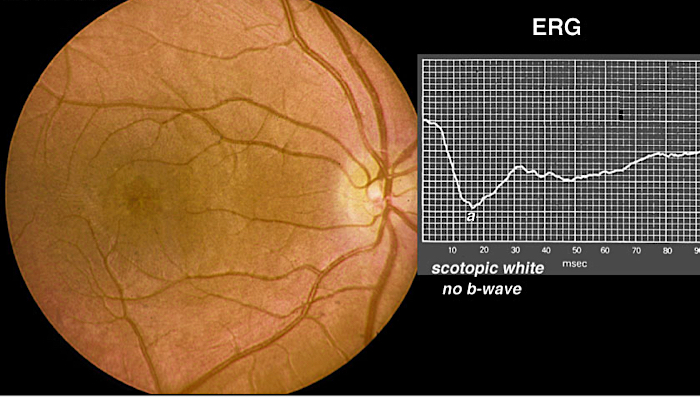

What’s an ERG?

The electroretinogram, usually referred to as an ERG, is the traditional diagnostic test for the genetic disease Leber’s Congenital Amaurosis (LCA). You can learn more about LCA here. The ERG measures the retina’s response to different light stimuli. If you are the parent of a baby or young child who has been tentatively diagnosed with LCA, your doctors probably suggested that your child have an ERG in order to confirm the diagnosis. You’re probably wondering what the test is like and whether or not you should do it now. I will explain what the test was like for our family and hopefully this will help you make your own decision.

First, it’s important to know that some families do choose to skip the ERG altogether. Some families decide not to rush into any invasive eye exams while others opt to rely on genetic testing instead, which is becoming a more and more reliable diagnostic tool as more LCA-causing genes are discovered. However, genetic testing can take a long time (our results took eight months to get back to us) and a negative test result through genetic testing does not mean that your child doesn’t have LCA—all a negative result means is that none of the known gene-mutations that cause LCA were found in your child’s blood sample. Scientists believe there are still quite a few undiscovered gene mutations out there.

The ERG, on the other hand, provides immediate results. Your doctor should be able tell by the wave forms produced from the test whether or not your child has LCA. I say “should” because there is a bit of interpretation involved. In our son’s case, we had quite a few doctors look over his results and they all decided that he most likely had LCA, but they definitely left us with the impression that an ERG is best read by a someone with experience with the disease.

LCA patients usually produce what is called a “flat” ERG. This does not mean, however, that the patient with LCA can’t see anything. Many patients with LCA do have light perception or light projection and some report being able to make out shapes and movements. All of them, though, would still have a flat ERG. In other words, you shouldn’t go into the ERG thinking that this test will tell you what your baby can or can’t see.

The actual procedure for the ERG differs from hospital to hospital and the experience is different for each patient. We had our ERG performed at the Cleveland Sight Center on July 28th, 2006, when our son, Ivan, was thirteen months old. Our doctor had recommended the ERG when Ivan was only three months old but we wanted to wait until he was a little bigger before we went through with it. In our case, we had to travel out of state because ERG’s aren’t performed on children younger than thirteen years (yes, thirteen years) in the state of Hawai’i. We also felt that Ivan would handle the test better as he got older. I’ve heard from other parents, though, that the test is much easier to perform on younger babies because they can’t fight back as much. Of course, others argue that ERG’s are much more accurate when performed on older children. This is definitely something to take into consideration.

Ivan’s ERG was scheduled for 7:45 am and he wasn’t allowed to eat or drink beforehand. The technician put drops in Ivan’s eyes while we waited so that his eyes would begin dilating. Once dilated, Ivan and I were brought to a very small, very dark room with one little red light. Here Ivan was given Versed, a light sedative that was supposed to make him calm and weak without knocking him out. We sat in the dark with the nurse and technician waiting for the Versed to take affect and Ivan’s eyes to adjust to the dark.

Ivan’s ERG was scheduled for 7:45 am and he wasn’t allowed to eat or drink beforehand. The technician put drops in Ivan’s eyes while we waited so that his eyes would begin dilating. Once dilated, Ivan and I were brought to a very small, very dark room with one little red light. Here Ivan was given Versed, a light sedative that was supposed to make him calm and weak without knocking him out. We sat in the dark with the nurse and technician waiting for the Versed to take affect and Ivan’s eyes to adjust to the dark.

The use of sedatives during the ERG, by the way, is a bit controversial. I’ve heard some doctors say you shouldn’t sedate at all if you want accurate results. Others say it’s OK to be completely asleep and that it’s easier on the baby. Our doctors decided on a middle route where Ivan was supposed to be calm but not asleep. Unfortunately, not all people react the same to Versed. Ivan, instead of getting tired, became very alert and chatty.

After twenty minutes they decided to give Ivan another dose of Versed. He never did get as tired as they wanted, so we had to go ahead with a slightly calm but still very strong baby. First they taped electrodes to his right wrist and forehead. Next, they placed numbing drops in his eyes and used large yellow contact-like braces to hold his lids apart. The center of these contacts were open and two more electrodes were applied, one on each eye. These contacts and electrodes were then taped to Ivan’s face. He had so much tape on his face, all you could see were his eye lashes, nose, and mouth. The contacts are designed to hold a baby’s eyes open during the procedure but Ivan’s lids kept slipping shut. It’s very hard to keep a squirmy baby calm and his eyes open!

The ERG takes place in a large box with an opening in the front for the face. In the box is a smooth white dome with very bright lights positioned around it. Ivan’s face was held in the box by the nurse (my job was to hold his hands) while the lights flashed and strobed. Mostly Ivan cried, but sometimes he laughed. They said that was a normal reaction to the drug. The technician had some trouble capturing Ivan’s “baseline” (another indication of how hard it is to perform this test on a baby), but after about twenty minutes it was all done and we were free to go sit in the calm-down room. When they let us leave, Ivan was exhausted (the picture to the right shows Ivan right after the exam).

The ERG takes place in a large box with an opening in the front for the face. In the box is a smooth white dome with very bright lights positioned around it. Ivan’s face was held in the box by the nurse (my job was to hold his hands) while the lights flashed and strobed. Mostly Ivan cried, but sometimes he laughed. They said that was a normal reaction to the drug. The technician had some trouble capturing Ivan’s “baseline” (another indication of how hard it is to perform this test on a baby), but after about twenty minutes it was all done and we were free to go sit in the calm-down room. When they let us leave, Ivan was exhausted (the picture to the right shows Ivan right after the exam).

Looking back, I’m very glad we had the ERG done when we did. Ivan was old enough to handle the exam but still young enough to forget it pretty fast (the Versed is also supposed to help them forget the ordeal). I’m also glad that we were able to get the information from the ERG and meet with a team of brilliant doctors while we were in Cleveland. I do hope that this information will help you decide whether or not the ERG is right for your family.

For more information about ERGs and how they are conducted, check out this video:

Related Posts

Eye Conditions and Syndromes, Visual Impairment

Neuralink Announces Plans to Restore Sight to the Blind with Brain Chip

Elon Musk’s company Neuralink has announced plans to begin human trials of its new “Blindsight” brain chip by the end of 2025.

Eye Conditions and Syndromes

Does Screen Time Affect Kids’ Vision?

Too much screen time can affect kids’ vision by causing eye strain, blurred vision, dry eyes, and even nearsightedness in children and adolescents.

Eye Conditions and Syndromes, Support, Visual Impairment

Coping with a Diagnosis: Emotional Support for Families with Visually Impaired Children

Families with emotional support are more resilient. Learn how to establish emotional support with peers, professionals, and the community to help your family thrive.